How can you change the world?

To purchase a copy of

A Riddle from the Good Mountain,

click here.

Soon after I finished The Cloudmakers in 1996, I wanted to write about another aspect of old-fashioned bookmaking: letterpress printing. My idea was to write about Johannes Gutenberg, who in the mid 1400s invented movable type and revolutionized the way books were made—not copied by hand but printed on a press.

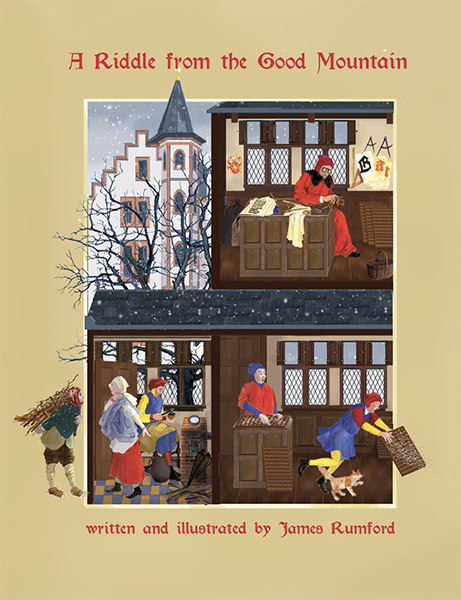

The idea that came to me was to construct the book as series of riddles: what was made of rags and bones, soot and seeds? What wore a dark brown coat and was filled with gold? What took lead and tin and a mountain to make?

The result was a look at bookmaking in the mid-fifteenth century. I had a few ideas how I would illustrate the book, but I made no sketches. I put the manuscript away for many years until Neal Porter at Roaring Brook Press showed an interest and offered me a contract.

I was delighted, but at the same time, I was a little anxious. I had no real idea how I wanted to draw pictures for such a complicated book. Why complicated? Because in the years since I had written the manuscript, the world of bookmaking had undergone enormous changes. The computer was taking over much of what Gutenberg had invented. Type was digitized and it was set on a computer. Even the printing was done on giant machines run by computers. And to top it off, books made of ink and paper were being supplanted by e-books and contraptions like Kindle. It was a new world; a new revolution was brewing, much like the one started by Gutenberg in 1450. How would kids brought up in this new age understand type and ink and letterpress printing? It's as if books were becoming like dinosaurs—extinct!

Not only are books changing, but the very libraries that house them are too.

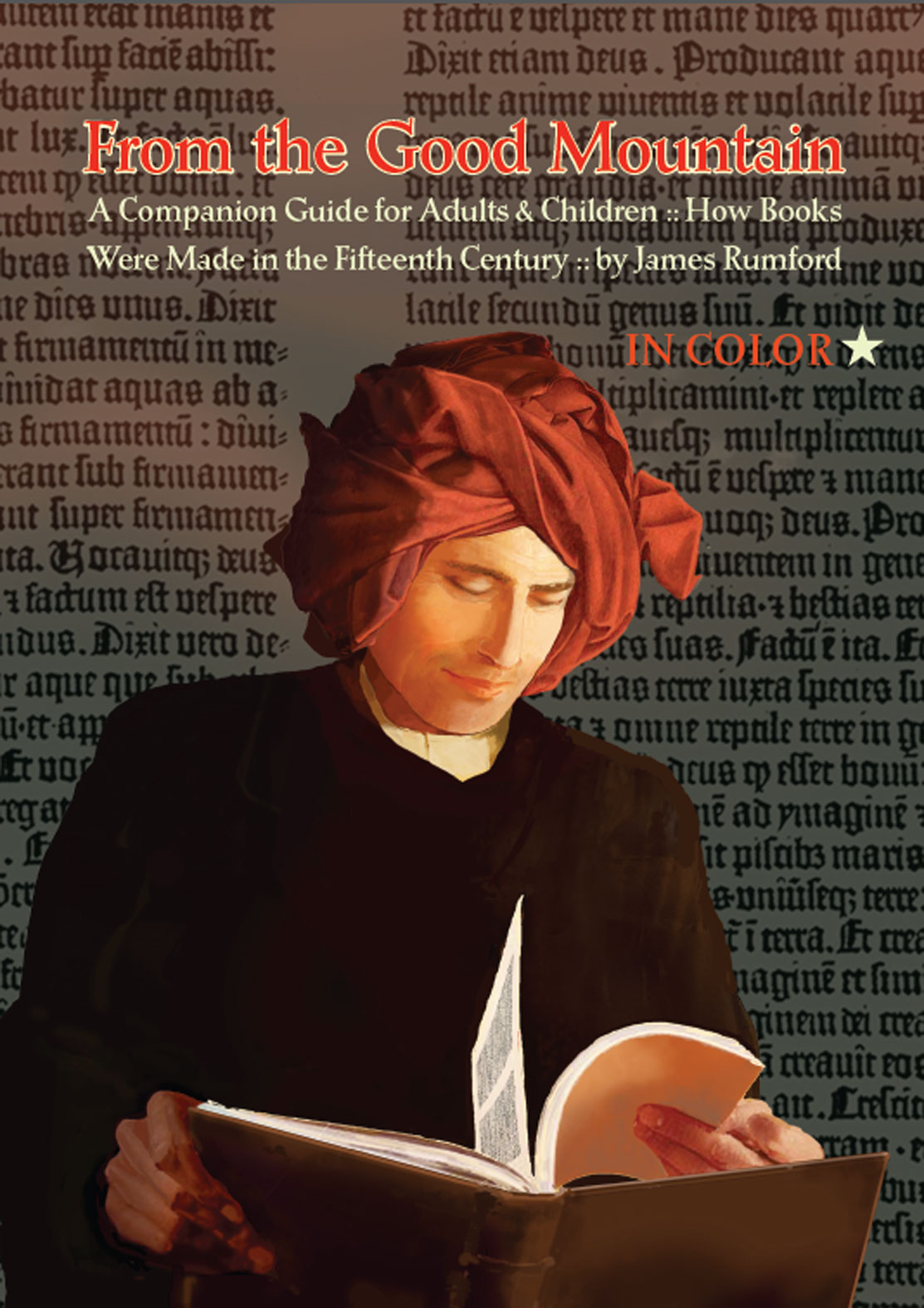

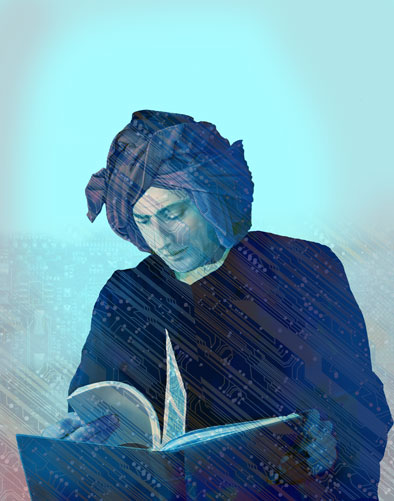

This realization gave me an idea. I decided to illustrate the book as if it were an illuminated manuscript from the fifteenth century. I would make the look of the book as old-fashioned as it could be so that kids today could feel what it was like to hold a richly ornamented book in their hands. On each two-page spread I decided to show how each step in the bookmaking process was done—from paper making to gilding to typecasting and press-building. I would end the book by showing graphically how the old technology was being transformed into the new as I changed the gilded designs of the illuminated pages gradually into the circuits of a modern computer. To emphasize this, I painted a portrait of Gutenberg in the style of fifteenth-century illuminators on the front cover while on the back cover I digitally transformed the same picture into a portrait of a computerized man.

I also decided to use the illustrations to show what life was like in fifteenth-century Germany. The text talks of dampening the sheets with water. But where did the water come from? There were no taps then. Water had to be brought into town in jars on mules. In a similar way, I show the importance of candle makers for light and wood cutters for fuel. On one page, amongst the workmen, I show children begging for food. Such were the realities of life almost six hundred years ago.

A lot of research has gone into this book. Not only have I drawn on many scholarly works but I have also drawn on my own experience as the owner of a fine press [Mānoa Press] and a maker of limit-edition handmade books. I have also consulted with experts in the field of incunabula, the books printed between 1450 and 1500. I have taken this information and distilled it into a book that makes this now ancient technology accessible to young readers who are curious about how books used to be made.

How Did I Do the Illustrations? Since the illustrations were to be like the miniatures done in medieval manuscripts, I decided from the start to rely heavily on the computer. This gave me the freedom to break up the image and work on each element separately. Because I had so much freedom, I decided to start off by sketching the figures on plain white paper with vermilion watercolor. Sometimes, I didn’t even wait for the paint to dry before I began redefining the figures with a black ballpoint pen. When everything was dry, I scanned the image and used Photoshop to extract all of the vermilion, leaving me just the black line. This I corrected digitally. Sometimes I printed the image out at 10% opacity so that I could rework the black lines. When the line drawing was finished, I printed it out—again at 10% opacity—so that I could paint the figures with gouache. Next I scanned the colored illustration and touched it up in Photoshop.

The final step? To reduce the image and insert it into the scene I had created. The scenes were all composed in Photoshop.

At some point, I realized that I needed to make a file, which I labeled “vocabulary.” These were not word lists but images that I could use over and over. Below is my vocabulary of the windows I had created in Photoshop. These images I used again and again in the various illustrations in the book.

Thanks to the computer I was able to approximate the unique work of fifteenth-century illuminators.